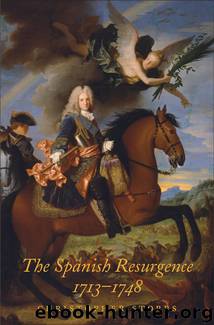

The Spanish Resurgence, 1713-1748 by Christopher Storrs

Author:Christopher Storrs

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780300216899

Publisher: Yale University Press

CHAPTER FIVE

FORAL SPAIN

By appointing as officers of the militia those most loyal to His Majesty, we can ensure that the nobility [of Valencia] serve His Majesty, which they are little inclined to.

—Marqués de Campoflorido, August 1726

The Spanish Habsburg Monarchy had been a composite polity, one in which the sovereign ruled a collection of territories, inside and outside Spain, which owed him obedience as ruler (king, duke, count, and so on) of that individual territory rather than as sovereign of a monolithic empire. Each territory had its own distinctive administrative, fiscal, legal, and other institutions, and the ruler was expected to respect these. This did not prevent the prince, resident as he was in Madrid, from drawing on the resources of those territories in pursuit of Monarchy-wide objectives. Nevertheless, it has been suggested that the failure to develop a coherent theory or justification of empire before 1700 helped ensure that few of Philip V’s subjects in Spanish Italy mourned the end of Spanish dominion in 1713. The most striking example of this quasi-contractual relationship was in the Crown of Aragon—comprising, in peninsular Spain, the realms of Aragon and Valencia and the principality of Catalonia—where the authority of the monarch was much weaker than in Castile. Failure to respect the laws and practices of those territories, the so-called fueros, might bring serious political consequences, as the Catalan revolt of 1640–52, which almost destroyed the Monarchy, shows.1

The polity which emerged from the War of the Spanish Succession was very different from that which Philip V inherited. Besides the territorial reconfiguration implied by the loss of Flanders and most of Italy and that of Menorca and Gibraltar in Spain itself, the Crown of Aragon lost its quasi-autonomy. For many subsequent commentators, this meant that Spain was emerging as a modern, nation-state, what Ricardo García Carcel has termed a vertical as opposed to a horizontal Spain. Indeed, the hostility of some historians to Philip’s Italian ambitions in part reflects a view that he was deviating from the path of modernisation, although that is to apply to the eighteenth century the concerns and criteria of a later age. A proper appreciation of what Philip and his ministers attempted and achieved has also been bedevilled by the fact that the reign and particularly its impact on the Aragonese territories remain a political battleground in a Spain in which regional autonomy and national identity are still matters of fierce debate.2

Philip V’s Mediterranean ambitions and the survival of foral regimes in Spain (Navarre, the Basque country) suggest he was not trying to create a modern, national realm, preferring instead to resurrect the old, supranational Habsburg Monarchy. However, his revanchism did not embrace all parts of that polity equally. It certainly included, for example, Spanish Flanders, itself a composite territory, into which considerable resources had been poured in the previous two centuries. An abortive project to establish there the princesse des Ursins in the peacemaking in 1713–14 implied maintaining a Spanish foothold. The scheme was abandoned after the arrival in

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Waking Up in Heaven: A True Story of Brokenness, Heaven, and Life Again by McVea Crystal & Tresniowski Alex(37781)

Still Foolin’ ’Em by Billy Crystal(36344)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32538)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31935)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31925)

Fanny Burney by Claire Harman(26591)

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(23069)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19032)

Hans Sturm: A Soldier's Odyssey on the Eastern Front by Gordon Williamson(18564)

Plagued by Fire by Paul Hendrickson(17401)

Out of India by Michael Foss(16843)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(15925)

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15324)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14476)

Molly's Game by Molly Bloom(14130)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14046)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(13866)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13306)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12363)